The present work is protected by copyright in all its parts.

© 2020 by Heinz Hermann Maria Hoppe.

All rights reserved.

Comment

Author: Heinz Hermann Maria Hoppe

Our work, unlike a thing, is never ‘finished’. Endlessly our daily efforts repeat themselves. With the change of day and night we get up and go to sleep. We take in food and consume our energy again in the company. We manufacture and consume in return.

For the downtrodden, work becomes torture. Their only reward for the endless repetitions of drudgery is fertility. They multiply their money and themselves. Perhaps they can afford children, who then grow up for years. If the reward is too small, their life turns into misery.3

Working and resting are like nature’s metabolism. The alternation between exhaustion and regeneration can make you happy.4 Most people seek meaningful tasks, the ‘happiness of work’. We even have a right to work and to strive for happiness. The unemployed, on the other hand, are perpetually exhausted. Those who stop working lose their liveliness. Listlessness spreads. Even the deserved pleasure as a self-reward for the efforts fades away. On the other hand, those who are rich and not or no longer need to work are bored ‘to death’.5 Man needs meaningful occupations.

Who is rich and does not have to work (anymore)Respect for work to provide for basic needs is a modern phenomenon. In ancient Greece, only slaves went to work in order to survive. Only unfree were compelled to earn their living as carpenters, scribes or as fishmongers. In a free profession, as a physician, as a farmer or as an architect, one enjoyed instead a good reputation. Productive and semi-skilled work, like the professions of ‘desk clerks’, laborers and craftsmen, is undergoing an image change.6

Objects of use consist of ideas, materials and actions. The work with our hands, the ‘craftsmanship’, was a prerequisite for the evolution of things. ‘Production’ and ‘productivity’ are teamwork between head and hand. Mental work is ‘unproductive’ in the strict sense of the word. It creates ‘products’ that can be consumed, but not touched.7 Such immaterial products, like software and entertainment programs, are taking up more and more space. ‘Digitization’ is the relocation of analog actions and things into the virtual world. Just as ‘digital twins’ are virtual representatives from the real world. They are simulations of design and manufacturing, of product life cycles; they can be used to interconnect product information from real spaces on a virtual level. Digitization can create competitive advantages.

The idea of being able to manufacture even faster through division of labor turned workbenches into assembly lines. But hungry workers continued to bring home meager wages through the sickening air polluted by steam engines in Manchester, England - despite (or precisely because of?) the Industrial Revolution. The benefits of technological progress flowed past them directly into the pockets of the factory owners.

Henry Ford’s assembly lines and the perfection of the division of labor with the same hand movements over and over again were consistently conceived. The idea of division of labor is also decisive 200 years later for the mechanical movements of metallic gripper arms. Today, robots again have more ‘degrees of freedom’, their ‘hand movements’ follow complex program line sequences.

Actually, machines were supposed to free people from undignified work.8 Since the invention of the steam engine, however, people have been and still are slaves to technology. In factories, human handouts are reduced to auxiliary work for press tools and lathes. Human intervention follows the beat of the crankshafts, not vice versa. The rhythm of the machines, which you have to keep up with, regulates the pace of work. Who does not come along, must go. ‘Cobots’ are supposed to support people at work again with the same arguments. Or is it the other way around?

Friedrich Engels, who grew up sheltered, observed the goings-on on the ground in Manchester at the time from a completely different perspective than a worker. As the scion of a textile industry entrepreneur from Barmen near Wuppertal, he analyzed the consequences of the physical and mechanical reproduction of labor power.9 With his influential study “The Condition of the Working Class in England” (1845), Engels was among the pioneers of empirical sociology with the theorist Karl Marx from Trier, he designed and propagated socialist and communist manifestos that would make world political history. In “Capital. A Critique of Political Economy” is about labor, yield, profit, and the potential power of the working class.

In her work “Vita activa”, Hannah Arendt examined the basic features of labor based on Marx’s theories. According to this theory, the cooperative organization of employees and machine support multiply the ‘fertility’ of companies, which can thus churn out more consumer goods. It is in cooperation that the finished product emerges; no worker alone brings together ‘a whole’ anymore. ‘Atomized’ work steps are more efficient, but they also leave a “gap in meaning”. There is less motivation to perform the same, dull tasks over and over again.10

Our current, positive ‘image’ of work advanced from the lowest level necessary for life to a valuable activity after it became clear that work can become the source of property and wealth. Marx defined ‘productivity’ as what remains after a worker has fed his family. He set two poles: ‘productive servitude’, which was opposed to ‘unproductive freedom’. These opposites appear unresolved against the background that, on the one hand, Marx wanted to liberate the working class from labor and emancipate it through revolution, but on the other hand, he metaphorically equated labor with necessary, natural life processes, such as procreation and birth.11

Working and learning are mutually dependent. The best jobs go to those who can call up special knowledge quickly and precisely when it is needed. Those who grasp things faster and have grasped a lot of material make the decisions. Equipped with precisely these competencies, new, very fast and inquisitive masters of learning are entering the market: algorithms.

Everyone is talking about digitization, and the learning process itself is also becoming digital. Communicating, manufacturing and distributing are being transformed in modern work processes. Almost every discipline will change, including creative and intuitive ones. In some companies, automated learning already begins with the first customer contact. Anyone who doesn't join in the general praise of digitization is considered backward-looking. Although the planned processes will reduce our ‘real’, analog life, it is better not to question them further. After all, you want to be seen as progressive, even if you have no concrete idea of what digitization actually means.

Nevertheless, most people believe that digitization only brings economic benefits and entirely ‘new jobs’. Digitization is the new ‘mantra’ of politics and industry. Rationalization, however, is usually accompanied by job cuts! Shouldn't we also name the disadvantages more clearly and discuss its social consequences more broadly?

Aren’t there still many more printouts of e-communications piling up in the filing cabinets of ‘paperless offices’, the contents of which were not even put into written form beforehand? Isn’t there a copier or a printer in every office? Analog [sic!] a ‘digital twin’ does not replace the comprehensible counterpart, but puts an additional version into the (virtual) world. Nor do virtual workpieces and tools necessarily make less work on the bottom line. Who guarantees us that the immense investments in digitization will not only benefit the ‘digitization industry’?

Artificial intelligence recognizes patterns. This sounds abstract, but it can be applied in a very concrete way. You can use AI for data matching of disease patterns down to genetic levels, for searching for court rulings in the jungle of laws, for logistical route planning, for machine control in manufacturing, for testing in quality assurance, even for seemingly intuitive ‘human’ tasks such as entertainment, care or creativity. ‘Digitization’, ‘machine learning’ and ‘robotics’ intertwine and will change most fields of work.12 Step by step, we are getting an inkling of the opening possibilities of self-learning systems. Implemented insidiously, the consequences will only become apparent with a time delay and ‘automatically’ entail the next ‘logical steps’.

Or are they still coming to their senses? According to an unpublished study, assumptions by the AI community have been confirmed that AI is always better at parroting but has nothing to do with actual understanding, would lead to social injustice and is obscenely harmful to the environment.13 Who actually forces us to uncritically accept and implement everything we could do – as if technological innovations had control over our lives in the name of the ‘social market economy’?

An alarming number of people are dissatisfied in their jobs. They hate the meaningless routines, the hamster wheel in which they turn in circles every day ‘nine-to-five’, the workload, the bureaucratic structures, the hierarchies, the bullying. It already starts with the stress on the way to work. The question of the meaning of one’s own actions often remains unanswered for an entire professional life and is continually postponed. The idea of taking control of one’s life, shaping one’s own days and turning dreams into reality has become alien to them. The risks of an insecure job are shunned like the devil shuns holy water, even by young professionals. The timed steps of the career ladder stand in the way of trial and error and self-discovery.

Most people therefore divide their lives into working time and leisure time, their goals into consumer goods and possessions, and they postpone the real, happy life until retirement. They have read about the fact that money does not make people happy, and they say it themselves with conviction. Nevertheless, they want to have as much of it as possible. They no longer have any idea what to do with themselves. What do these people do in their time when they retire – or when their work will no longer be there for them every day as a matter of course, even in middle age?

An employer exchanges a job and wages for the labor of an employee. The assumed work is done with power and rewarded with money. The money received has purchasing power, but the parties have fundamentally opposite interests. Employers want as much of the force as possible for as little pay as possible. Employees want as much pay as possible for as little of their power as possible. After all, they still need their energy for personal growth after their work is done. For them, work and money are a means of living; for the entrepreneur, labor is a means of increasing capital. Growth at any price has different signs on opposite sides.

If the employee could realize himself during work, as in his private life or as a self-employed person, he would grow better through his work and the interests would no longer be so opposed. Self-realization during work is therefore not a luxury problem, but increases productivity. But where there is no work at all, claims to self-realization, such as the general right to work, degenerate into phrases.

A few software monopolists and small consultant special units control more and more production lines in factories that are almost devoid of people. Algorithms, robots and automats are predictable, they don’t get tired or sick, they work in unison, without vacation or overtime reduction, in three shifts, loyal to the company for the duration of their product cycles.14 What will become of the workers?

Manual labor has long been a thing of the past in many production steps, but mental labor will also become increasingly unimportant. Human qualities are becoming dispensable; pure functioning is what is sought after.15 Older employees are often no longer able to keep up. Too slow and too cumbersome, they can no longer constantly reinvent themselves and are no longer needed. At best, they are sent into early retirement, otherwise they tear both legs out. Like many ‘freelancers’ who somehow make ends meet in precarious and temporary employment relationships, without protection against dismissal, provided only with contracts for work or committed to seasonal unskilled jobs, like day laborers. These people will not find a workplace for life, not even a profession for life, but will have no perspective for any form of working life from the very beginning and will sink into insignificance in the long run.16

However, unqualified and destitute ‘customers’ are also economically uninteresting. What happens when the gap widens further and people are not even ‘useful’ as consumers? What will our societies do with the many ‘superfluous’ people? And what do they do with themselves if they were used to detailed instructions and sets of rules in their previous jobs?17 Mass discontent leads to discord.

This is not the first time that fears of mass unemployment have been downplayed. Leaving aside the many fates of future unemployed, the argument is that new technologies have always created new jobs and prospects. Technological developments could not be stopped anyway. ‘They just have to retrain.’ What the ‘simple worker’ is supposed to do in the future remains unanswered. Meanwhile, he continues to hope that he, of all people, will continue to find work in his niche, because vending machines are not yet profitable there.

We believe, everything must grow naturally always, like the blooming nature. Income, savings and goods are supposed to multiply infinitely.18 When there is an impending ‘shortage of food’, the fun finally stops. A half-full refrigerator does not work at all. Hunger is unknown to us, except during self-imposed diets due to our excessive BMI.

Growth without end is short-sighted, illogical, unnecessary and destructive. Already today, according to a scientific study, the mass of man-made products exceeds the world's biomass.19 We now consume commodities like food. Furnishings are changed like clothes used to be, following catalog fashions. T-shirts are like ‘coffee to go’.

The economy has a fundamental interest in the cycle of consumption and discarding. For more and more growth, it should circulate even faster. But the commodity cycle works much better than recycling. The production of our wealth goods consumes faster and faster, rarer and rarer resources for things that no one needs. In our society, we throw away almost as fast as it took to make them. Our wear and tear keeps a huge manufacturing and packaging machinery running 20

Shouldn’t we and don’t we have to go onlike this because of the jobs that depend on the manufacturing industry? Aren’t ‘jobs, jobs, jobs ...’ the overriding argument?

If 47 percent of the technologically developed countries in the West lose their jobs and more than seven hundred job descriptions are taken over, at least in part, by computers,22 the gap between rich and poor will widen even further. The metamorphosis of digitalization, with reduced offers of qualified jobs, will turn our society upside down. Not today, not tomorrow, but in the medium and long term.

What do we do all day long when work no longer has time for us? Do we simply compensate for the earlier movement at work with sports? What can we treat ourselves to and what do we enjoy when we haven’t earned consumption? How are we going to find meaning in meaningless activities? What do we have left but to play and ‘pass the time’? How do we satisfy our growing demands when we have much more time for desires, but resources are scarce? What do we ‘consume’ when we have already ‘sampled’ all the cultural goods? What does this do to our psyche? What will become of us?21

Or is the seriousness of life, the earning of money, finally losing its terror? Do algorithms and automata provide us with the longed-for lightness of being and finally the freedom for self-realization? Will working people become hobby artists, thinkers and players who meet in parks and philosophize about human nature? Could life without ‘duty by the book’ be the basis for cultural progress? But doesn’t effortlessly ‘drifting through the day’ make people dissatisfied in the long run? What is the new ‘bread’ and what are the new ‘games’ for the masses?

And who is supposed to pay for all this anyway – ‘basic security’ or ‘unconditional basic income’? How can we distribute the capital generated by robots fairly? Why should investors voluntarily give away their capital for our common good? Ideas for taxation and financing are not (yet) seriously discussed. On the contrary, working lives are to be increased to finance pensions. But the question of where the work for employees over 60 to 70 years old is to come from in the future is not answered.

People who are once again more self-reliant, who grow, build and repair products for their own use instead of throwing them away, are united by a feeling of happiness. This is in contrast to our gadget culture, because technical development, as dreamed up and preached by Silicon Valley, does not turn us into ‘supermen’, but into beings who can no longer do anything without tools. Our manual skills are extinguished, our linguistic expression is reduced, our memory, outsourced to memory functions, is diminished, our imagination consists of prefabricated images, our creativity follows exclusively technical patterns, our curiosity gives way to convenience, our patience to permanent impatience; we can no longer endure the state of non-amusement.23

Those who no longer feel useful, whose time is no longer worth any money, who can no longer buy everything at will, are forced to ask core questions of themselves anew and to reflect - or give in. If such questions only arise at the end of your life, you have lost your chance of finding timely answers for a happy life. What do you need for a happy life?

We age from the time we are born. Before we reach the middle of our lives, our growth ends and decay begins. If you live to be 80, you have lived 691,200 hours. What do you work for? How many hours do you have to work? How many hours of that do you enjoy working? How dependent are you on your work? Can you achieve your life goals even if you reduce or lose your work? How dependent do you want to be on luxuries and consumer goods? What do you want to own? What would set you free? How sick does your job make you? How much do you enjoy your job? What do you do when you are bored? Are you, perceived, getting ahead or have you been treading water for a while? What counts for you in the end?

Will we need an agency for self-realization in the future?

What would you do with a life without work?

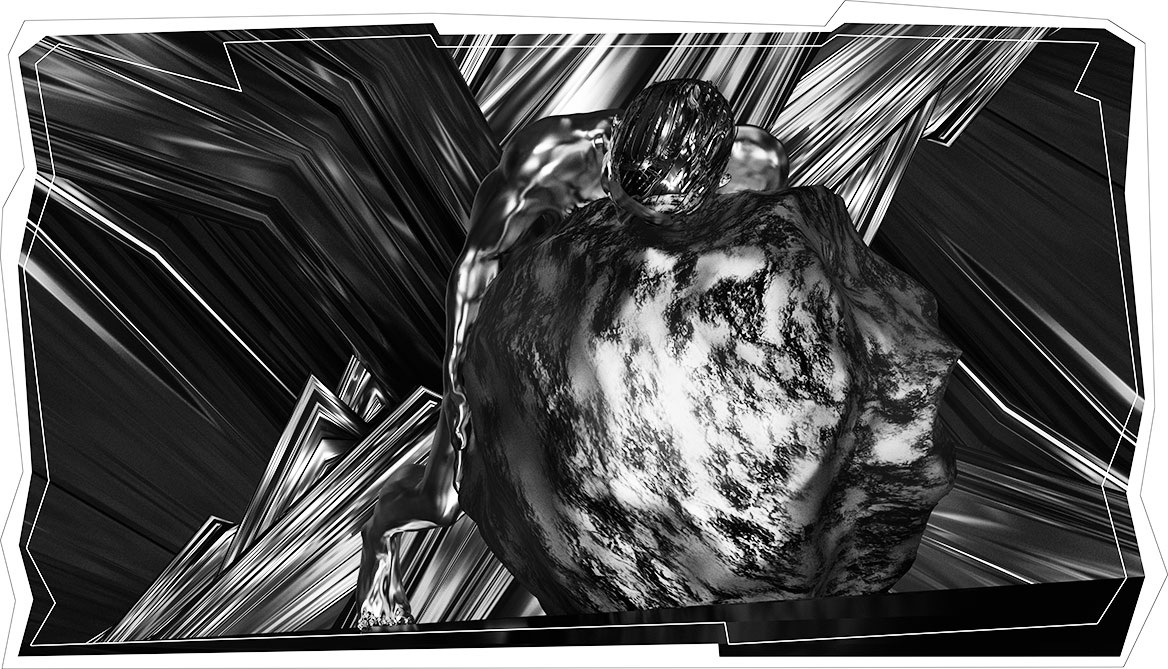

Titian created a muscular Sisyphus between 1548 and 1549, Franz von Stuck painted his version in 1920. Albert Camus, ‘philosopher of the absurd’, revived the legend with his stage play “Caligula” (premiere 1945) and with the novel “The Stranger” (“L’Étranger”, 1942). His treatment of existentialist questions in “The Myth of Sisyphus” (original title: “Le mythe de Sisyphe. Essai sur l’Absurde”) became world famous.2

Camus revived the endless torment of Sisyphus, which was variously interpreted thereafter. Erich Fried described in a Holocaust association the fear of Sisyphus for the wear of the stone. In GDR literature, working people of socialism find their solution in simply leaving the stone. In a poem by Fred Portegies Zwarts, on the other hand, Sisyphus pushes the boulder himself back into the abyss so that he can continue working.2

Camus concludes the “myth of Sisyphus” in his essay of the same name, surprisingly for a fate full of torment, with a positive image of existence: the struggle against summits is able to fill a human heart. We must imagine Sisyphus as a happy man.24

Why does an artist who himself works with digital tools and creates digital visual worlds question the current process of digitization?

Because digitization will change heavily on our future lives. Because there's no reason not to question it - whether with digital or analog art. Because digital tools can reproduce virtual spaces outstandingly well. But such tools and virtuality will not be needed per se in all working worlds.

List of German sources and literature:

1 Freely translated. See Harari, Yuval Noah: Homo Deus. Eine Geschichte von Morgen. C.H.Beck Munich: 10. Edition 2019, P. 415.

2 See Sisyphos. In: Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Date of last revision: January 2, 2021, 10:05 UTC. URL: https://de. wikipedia.org/w/ index.php?title=Sisyphos&oldid=207169179 (Date retrieved: January 5, 2021, 11:25 UTC).

3 See Arendt, Hannah: Vita activa oder Vom tätigen Leben. Piper Munich Zurich: Paperback special edition September 2002, P. 140 ff.

4 See ibid., P. 134.

5 See ibid., P. 126 ff.

6 See ibid., P. 104 ff. and P. 153.

7 See ibid., P. 107 ff.

8 See Precht, Richard David: Jäger, Hirten, Kritiker. Wilhelm Golfmann Verlag, Munich: 7. Edition 2018, P. 101.

9 See Friedrich Engels. In: Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Date of last revision: Dezember 21, 2020, 10:25 UTC. URL: https://de. wikipedia.org/w/ index.php?title=Friedrich_Engels &oldid=206753546 (Date retrieved: January 5, 2021, 12:30 UTC).

10 See Arendt, Hannah: Vita activa. P. 142 ff.

11 See ibid., P. 111–125.

12 See Harari, Yuval Noah: 21 Lektionen für das 21. Jahrhundert. C.H.Beck Munich: 2. Edition 2019, P. 49.

13 See Moorstedt, Michael: Papageienhirne. War Google die eigene Ethik-Expertin zu kritisch? in: Netzkolumne, Süddeutsche Zeitung No. 289 from December 14, 2020.

14 See Harari, Yuval Noah: 21 Lektionen für das 21. Jahrhundert. P. 49–57.

15 See Harari, Yuval Noah: Homo Deus. Eine Geschichte von Morgen. C.H.Beck Munich: 10. Edition 2019, P. 495.

16 See Harari, Yuval Noah: 21 Lektionen für das 21. Jahrhundert. P. 66–70.

17 See Harari, Yuval Noah: Homo Deus. P. 469–498.

18 See Arendt, Hannah: Vita activa. P. 124–126.

19 See Zeitalter des Anthropozäns. Künstlich hergestellte Produkte übersteigen weltweite Biomasse. in: Wissen, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Date retrieved December 9, 2020, 19:27 UTC. URL: https:// www.faz.net/ aktuell/wissen/ anthropozaen-kuenstlich- hergestellte-produkte- uebersteigen-biomasse- 17094486.html

20 See Arendt, Hannah: Vita activa. P. 147–158.

21 See ibid., P. 157–160.

22 See Precht, Richard David: Jäger, Hirten, Kritiker. P. 23–24.

23 Freely translated. See Precht, Richard David: Jäger, Hirten, Kritiker. P. 154.

24 See Camus, Albert: Der Mythos von Sisyphos. Ein Versuch über das Absurde. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag Hamburg: 410.–413. Thousand October 1999, P. 128.