This work is protected by copyright in all its parts.

© 2023 by Heinz Hermann Maria Hoppe. All rights reserved.

Color and tone value representations on monitors deviate from the original.

Comment

Author: Heinz Hermann Maria Hoppe

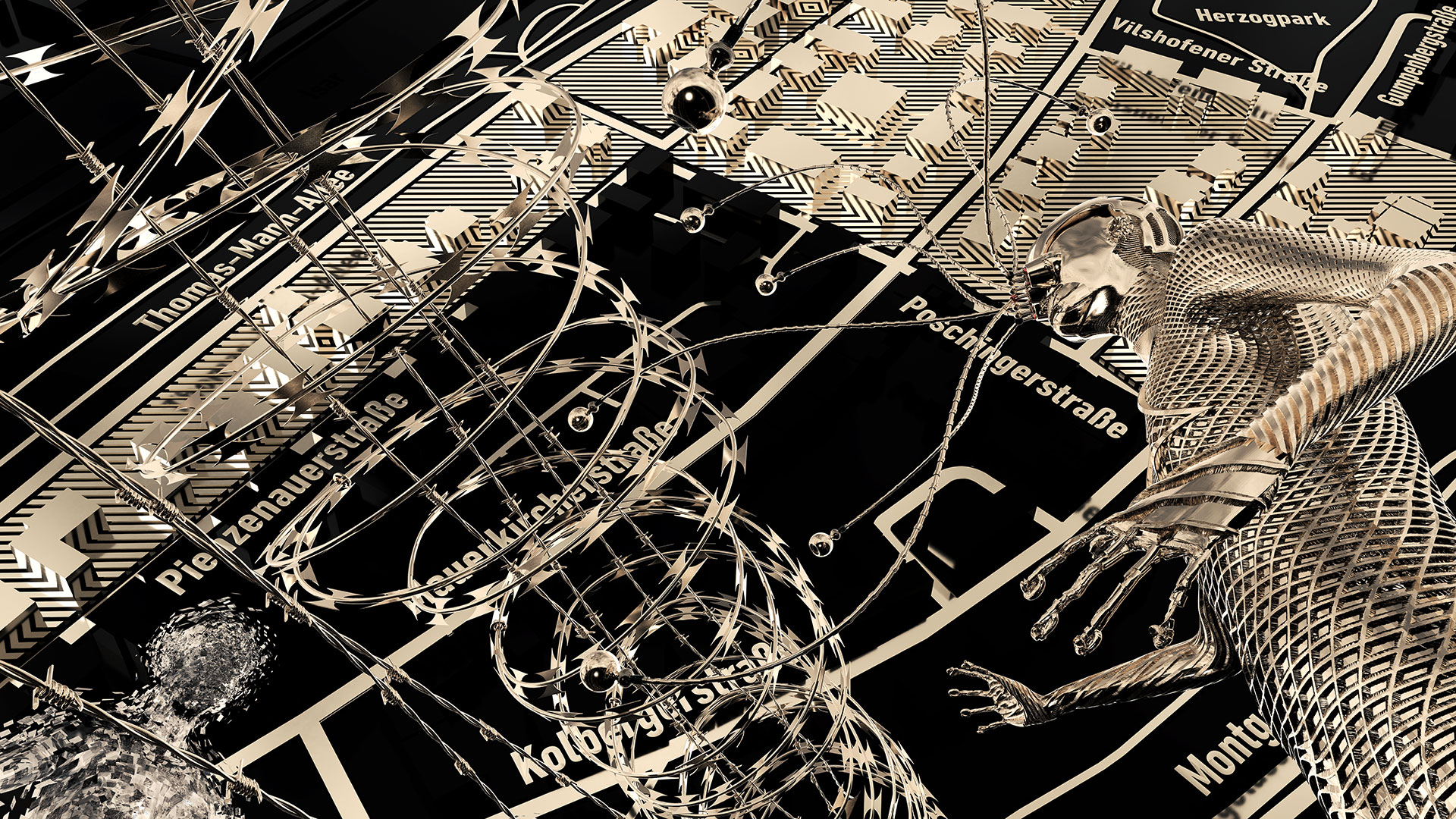

The urban is divided into zones. Cities are crisscrossed by networks of virtual borders. Invisible walls separate income strata. Prime locations contrast with run-down areas, ‘nostalgic nooks’ with the condemned ‘hovel miles’, allotments with the industrial estates, cobblestone old town centers with the ‘housing strongholds’. The milieus can be read at the facades, in the window displays, at the doorbell signs. Architectural styles of the gables mark immaterial boundaries. Beneath them, personal attitudes, levels of education and prejudices condense to form opinions. Social structures spread out like lichens, more or less interwoven with neighborhood structures. Behind the house walls, sometimes new ‘thinking drawers’ open up. But most probably remain firmly closed. Spaces are by definition encapsulated spheres.

Old quarters ‘made new’ attract the brokers of the intellectuals. The rich reside in defiant, but not necessarily tasteful villas, but in prime locations, on sunny lakeshores or near quiet parks. The elite keep to themselves in their bubbles. Account balances define personal traffic zones, clearly demarcated from the shady sides of multi-story concrete facades, the wiry building fences, ‘the filthy corners’, the ‘kebab and game stalls’ in desolate shopping streets, at a distance from the spray-painted underpasses, the overgrown green strips, and the rusty equipment on unimaginative playgrounds.

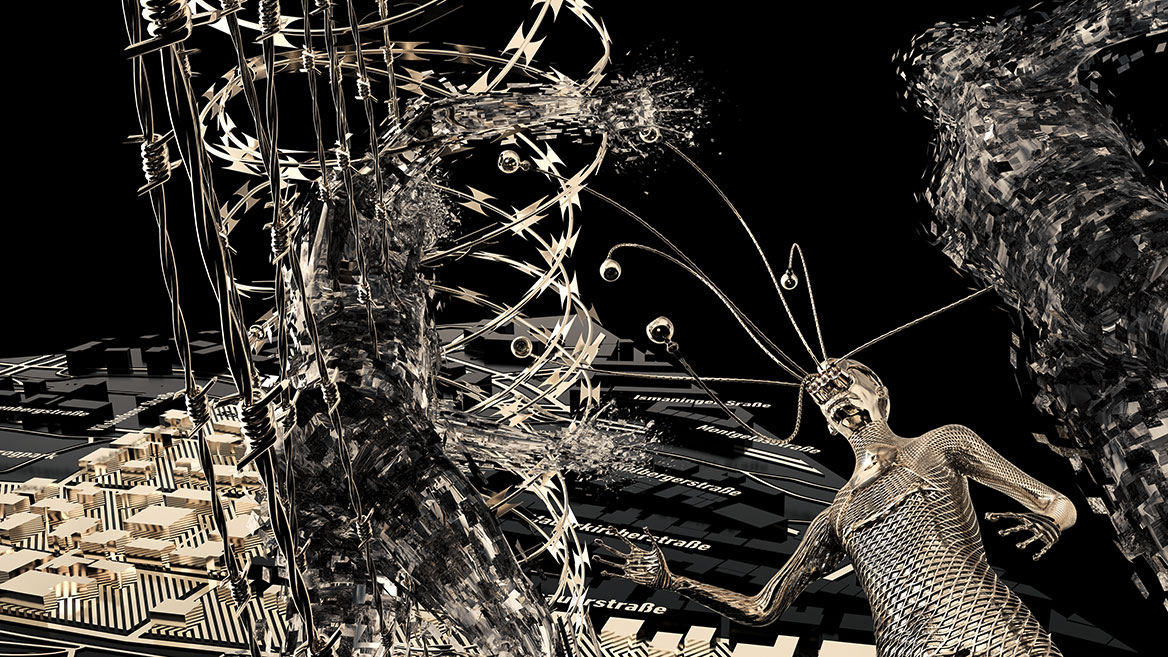

Land and real estate prices in central locations have become unaffordable for ‘ordinary mortals’. The price spirals of housing costs are swirling more and more strata of the population behind the transparent fences of the city district boundaries, into the confines of their wallets. Those displaced into inferior living zones form ‘new home bubbles’. ‘Underdogs’ remain among themselves even in the busiest pedestrian zones, even behind the main train stations, even in the disreputable harbor districts, en masse in the ghettos. Urban inhospitable places full of building sins are the same ones that locals avoid after dark and tourists even ‘in broad daylight’. This ultimately damages the reputation of the entire city and causes economic damage.

Early urbanism distinguished urban zones in winged words “according to the politeness of language, according to the prevailing spirit, and according to customs”. The developments of exploding populations in modern metropolises were addressed by the Chicago School, architects like Le Corbusier, and philosophers like Roland Barthes. It turned out that the street plans with their right angles, which became popular in America, did not necessarily lead to ‘upright attitudes’. Right angles ‘en masse’ nevertheless remain architecturally programmatic, the space utilization and cost advantages of the ninetieth degree are hard to beat. ‘Cages’ are angular, that’s why they meet the specifications and remain design law for living spaces even in the banlieues.

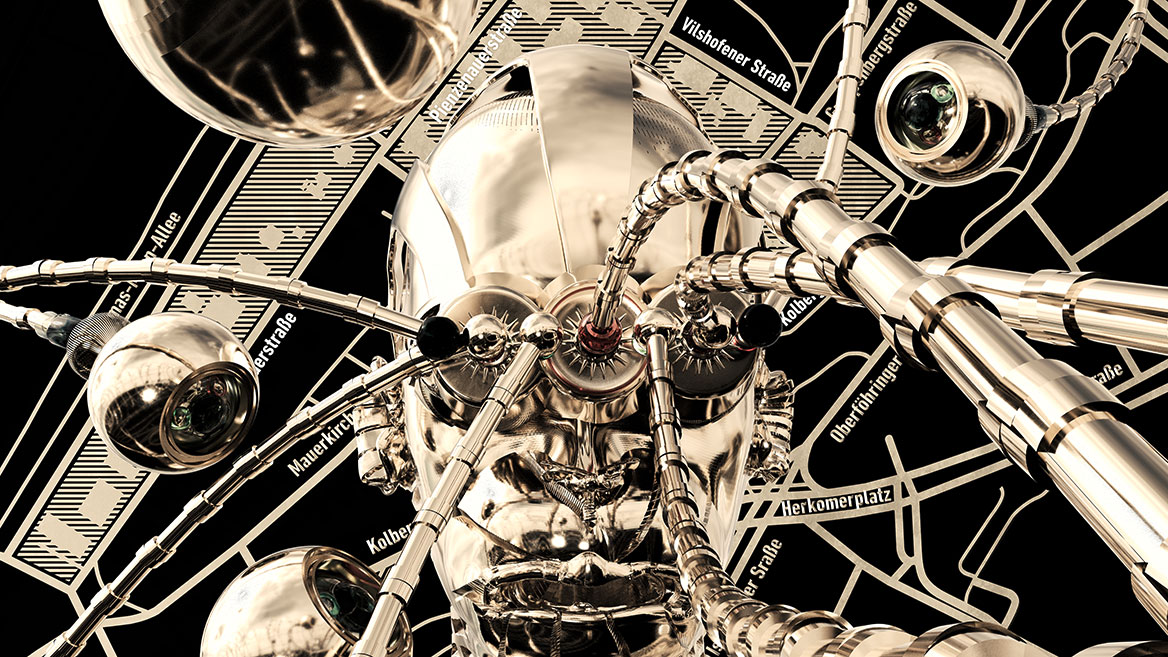

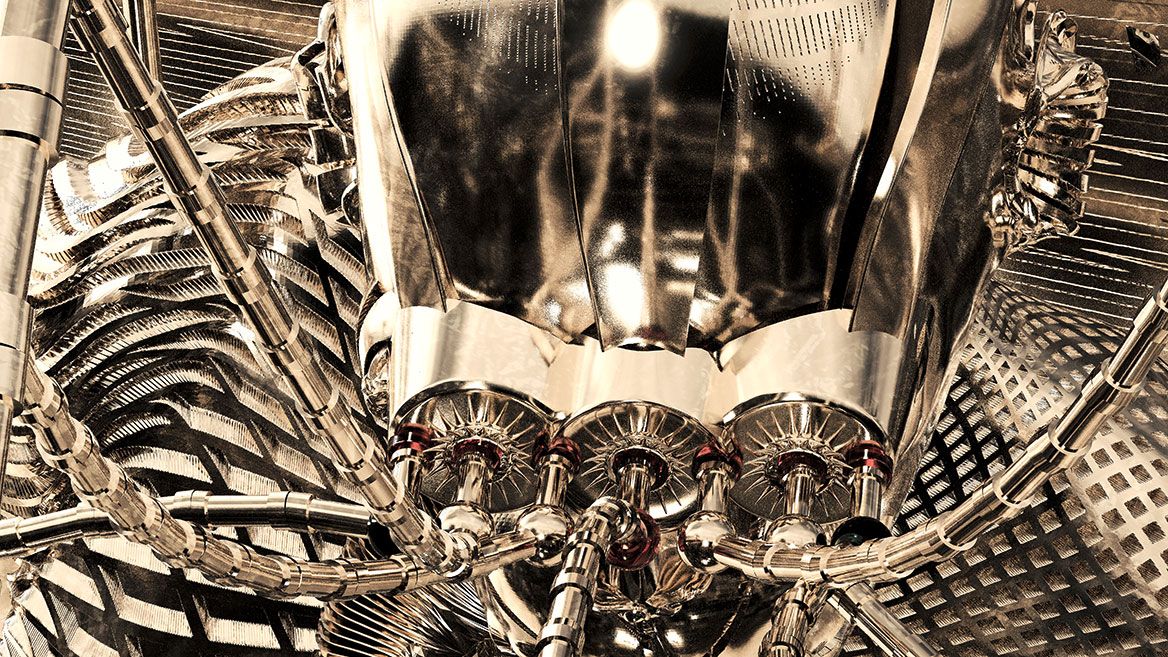

Only ‘the other side’ can afford a free formal language. “After all, one doesn’t treat oneself to anything else”. Where prosperity has erupted so exuberantly that one might think one is living not only in different hemispheres, but in different times. But freedoms also have their price: wealth goes hand in hand with the fear of losing one’s possessions. Markets created specifically for this clientele flourish, selling security products to satisfy needs. Security services, structural installations and high-tech surveillance for shielding and defense, motion detectors, scanners and thermal imaging cameras, lighting, control and communication systems, security doors, locking and alarm systems, safes and guns – against fear.

In the particularly insecure climes of this world, income millionaires invest their bonuses in security guards with shift duties, for access controls at the neighborhood gates, for reassuring feelings around the clock. ‘Green zones’ can be organized like city states: with their own electricity and communication networks, with autonomous drinking water and sewage systems, with excellently equipped hospitals, with luxury goods warehouses and sports centers – cities within cities, sometimes in the middle of ‘seas of misery and need’ (Naomi Klein, Die Schock-Strategie, S. Fischer Verlag 2007, p. 592 ff.). Voluntarily withdrawn behind barred windows, locking themselves into spacious spa areas, a carefree life seems to remain unaffordable even on the ‘winning side’. The luxury resorts fortified with Dobermans, ‘fortresses of wealth’ with graveled but inanimate driveways, also turn the occupants into mere ‘zone dwellers’.

Urban habitats can give rise to green utopias all the way to the fringes, or to ‘black paintings’ with ‘show facades’ and deserted ruins. Cities are living organisms whose clusters must continuously ‘shed their skin’. Inhabitants can ‘lively each other up’ or isolate themselves in bubbles and remain lonely. Depending on political and urban structures, cityscapes transform into sites of “[…] multiple, overlapping spaces, times, and webs of relationships […]” (Ash Amin/Stephen Graham in The Ordinary City, 1997).

‘Neighborhoods full of the damned’ and ‘settlements full of the hopeless’ abound all over the world – increasingly also in Germany. Those who have been ‘deported’ to farmland on the outskirts of cities are attracted even more to the city centers. An undignified life in overpriced ‘dwellings’ and exuberant fears of survival drive the poor into the streets and ‘onto the barricades’. Safe zones in or next to ‘no-go areas’ do not bring calm to heated minds. Our cities should be safe for everyone, not just the rich.

The increase in everyday worries also makes the tone rougher. Opposing interests, even within groups of the shamed, result in confrontations. The ‘upper class’ is outraged by those who remain at the bottom. ‘Unseemly behavior’, however, often arises not from too little, but from too much ‘pressure’. A ‘beating’ experienced on one’s own body makes one more aggressive. It is not true that anyone could ‘make it’ if they wanted to. The American dream remains for most, despite all efforts, only a dream for life. Poverty and ‘laziness’ are not a couple, resignation and illness are.

At some point, the majority simply accepts their living conditions and ‘ducks away’ – also out of fear. In ‘broken areas’ collective fear thrives and the call for more repression, for more police and for harsher punishments. Perhaps it would be much more beneficial to make the areas ‘whole’ again in other ways?

A veritable flood of new programs would have to be initiated, especially in the current times. Self- and citizen initiatives could ‘inspire’ to contribute to the beautification and planting of cities. Many more people than is commonly thought would get involved – if there was good choreography, if people saw a purpose in it, if they were allowed to do it on their own responsibility and with commitment, and if they had fun doing it. One could allow design pathways for people, rather than for new ‘mobility technologies’. Hardly visited museums and churches could be played in a new, different way by young and old. The old patterns of debate could be abandoned and ‘doubters’ could be overruled. Public places could be freed up for neighborly interactions ∞. Social ‘bubbles’ we could simply burst.

Who is supposed to pay for that? Counter-questions: What could be more expensive than the maintenance of representative sham facades, of unused halls and of empty squares? Who will pay in the end for the lack of flexibility and systems thinking?